Eric never thought he’d make it to 30. He began using heroin when he was 19, overdosing twice.

“There was no way I was going to make it through my 20s,” says Eric, now 33.

He almost didn’t.

Eric’s story has a happy ending: He hasn’t used an addictive substance in two years. He’s taking college courses, studying addiction psychology, and hoping to one day work with incarcerated men. He volunteers with Prevention Point Philadelphia, serving alongside the people, he says, who gave him food, clothing, and clean syringes without judgement and offered love and compassion when he didn’t think he deserved it.

“On a freezing cold night, I was always able to come here and get clothing and blankets and food. I’d go days without eating… and the meal I’d gotten in me had saved me,” he says. “In the middle of chaos, there is peace here.”

Eric started using drugs as a teen in Montgomery County. When he saw that he was hurting his family – “I never thought I’d steal from my mom, but that started happening.” – he moved to Kensington, “where it almost gave me as much satisfaction being down here in the mix as the drugs did,” he says.

He fell into a years-long cycle that went like this: incarceration, release, living on the streets and using drugs, getting arrested, and incarceration again.

Eric utilized Prevention Point’s services, but he didn’t understand the organization’s mission until he overdosed and a stranger revived him with Narcan that had most likely been distributed by the organization.

“That’s when, for the first time, I saw that harm reduction was real and it was important,” he says. “I’m pretty sure another addict (saved me). That was such a deep experience.”

Eric continued to live on the street, shooting fentanyl, which soon became contaminated with tranq.

“All my veins went away. My hands were constantly blown up. The sickness was unbearable. It’s every three or four hours and it’s throwing up constantly and diarrhea,” he says.

In 2022, Eric had had enough. He went to Prevention Point to obtain Sublocade. He also began taking its art therapy classes, which to this day “give me space to feel calm, relaxed, safe.” He made time for writing—something he’d begun during a prison stint.

Drugs, he says, allowed him to get into a zone where nothing bothered him, and he needed to stay high to stay there. “It doesn’t matter if it’s the train passing, somebody getting stabbed or shot at, nobody can affect that,” he says.

Now writing gives him the same feeling: “I can sit down and write and for three hours, I’m away from everything around me,” he says. He puts down the bad thoughts racing through his head and “it releases them for a lot longer than a shot of fentanyl or a hit of crack does.”

Eric is now a Prevention Point volunteer. One night, he and some other volunteers were setting up for Men’s Night when they got word there’d been an overdose. The volunteers, including Eric, ran to help. A man wearing a state prison uniform lay in the middle of the street, unmoving.

“Watching that guy’s eyes open after they Narcan’ed him, that’s something I’ll never forget… It was so deep and I was thinking, ‘My god, they just saved a life,’” Eric recalls. “And right after they saved a life, they went back to serving meals like nothing had happened… It was natural to them.”

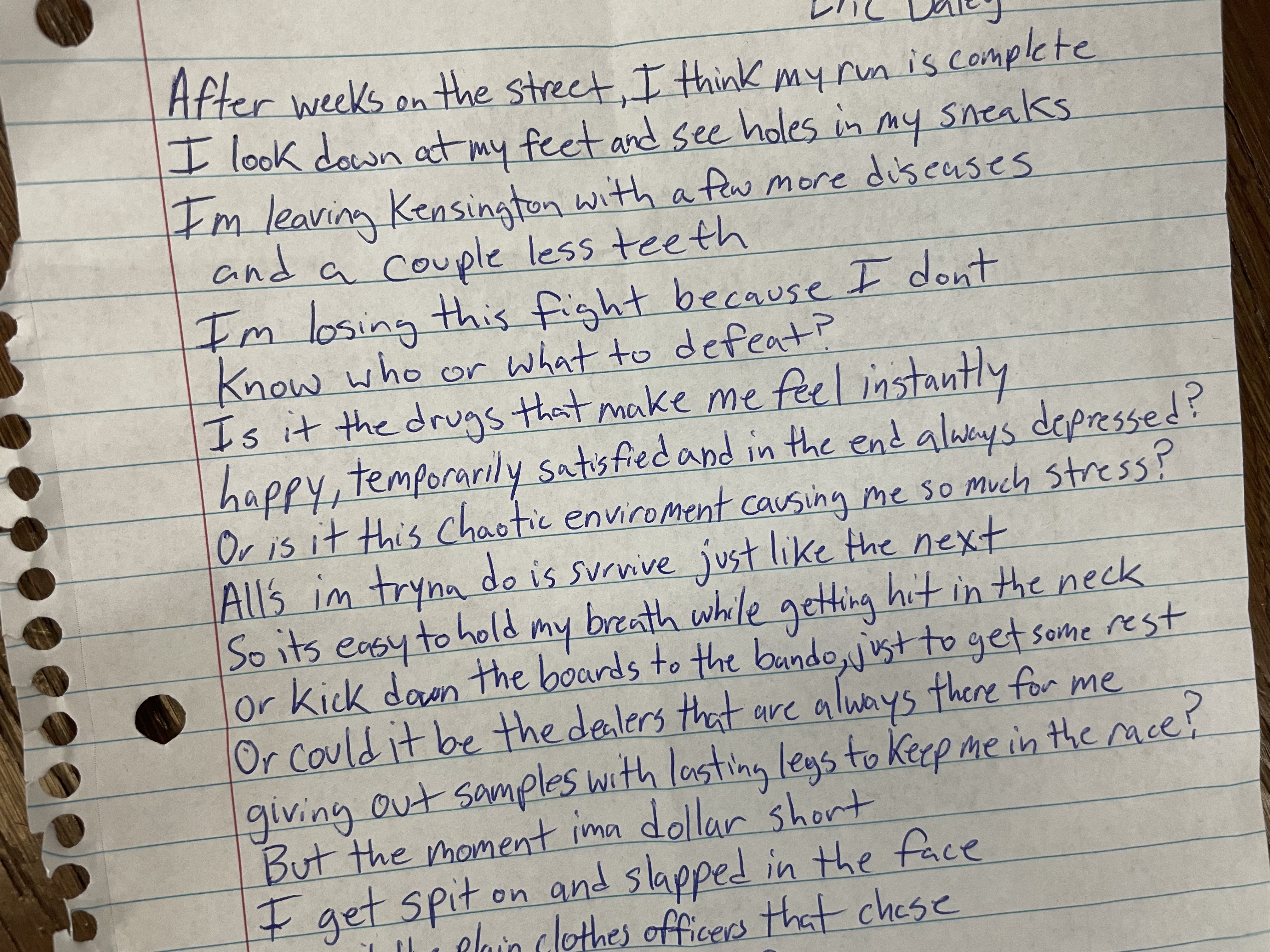

Eric shared a poem he wrote while he was still using drugs:

Stuck in the Game

After weeks on the street, I think my run is complete.

I look down at my feet and see holes in my sneaks.

I’m leaving Kensington, with a few more diseases

and a couple less teeth.

I’m losing this fight because I don’t

know who or what to defeat?

Is it the drugs that make me feel instantly

happy, temporarily satisfied, and in the end, always depressed?

Or is it this chaotic environment, causing me so much stress?

All’s I’m tryna do is survive, just like the next

So it’s easy to hold my breath while getting hit in the neck

Or kick down the boards to the ‘bando just to get some rest.

Or could it be the dealers that are always there for me

giving out samples with lasting legs to keep me in the race?

But the moment I’m a dollar short

I get spit on and slapped in the face.

Or is it the plain clothes officers that chase

me up and down the block?

They tackle me to the ground, handcuff me and take my rock.

And as we drive to the district, they just laugh and mock.

Then one turns around with a smile and says

your detainer just dropped.

But after repeating this cycle and over and over

nothing has changed. I walk out of jail

feeling exactly the same.

But then I think... maybe I’m the one to blame.

Maybe I’m the reason for all my pain.

Fuck it, I’m already on the train.

My mind and body filled with nothing but

guilt and shame.

As I get off at Somerset I don’t know

if I’m dead or alive. They both feel the same.

But I do know not to place blame

Because everything I went through was

part of the game.