Despite major advances in HIV/AIDS prevention, education, and treatment over the past 30 years, the epidemic continues to disproportionately impact certain populations. Determinants including systemic racism, economic marginalization, access to health care, and stigma all contribute to why HIV continues to have outsized effects on Black communities. According to the CDC, Black people accounted for 13% of the U.S. population but 40% of people with HIV in 2019.

February 7 marks National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. To commemorate this day, we spoke with several of Prevention Point Philadelphia’s staff working in HIV prevention and care who have observed the collective response to HIV evolve over the years in their Black communities.

Kareem Mims is the Coordinator of Prevention Point’s PrEP Clinic. PrEP stands for “pre-exposure prophylaxis”—a medicine that people at risk for HIV can take to prevent acquiring HIV from sex or injection drug use.

“I’ve been doing HIV work since 2005. I started in high school, mainly because my mother was affected by the AIDS epidemic,” Kareem says. “The Calcutta House is a shelter in North Philly for women living in the last stages of AIDS. The people that work there try to make those women as comfortable as possible. That’s where my mother died. So after she died there, I started volunteering there after school.”

Kareem was just 14 when he lost his mother, but she was always transparent with her son about what she was experiencing. “It was horrible, but I also think I got to experience it in a way that back then a lot of people didn’t,” he explains. “I kind of watched her transition. I was there with her every day. I was able to say goodbye. Back in those days a lot of people would just get a phone call or a visit from the police saying that their loved one passed away. But my mom was able to get into care and get the help that she needed at the end of her life. That’s what inspired me to do this work.”

As a volunteer, Kareem often heard families say that if they would have known about the importance of getting tested for HIV, they would have taken their loved one to a clinic much sooner. “Back then you didn’t know you had HIV until you had AIDS,” Kareem remembers.

National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day began in 1999, but Kareem says that the messaging around testing, treatment, and prevention took much longer to reach the communities most at risk. In Kareem’s experience, this was a result of a myriad of factors including:

- Methods of communication: Not everyone in 1999 and the early 2000s had access to a radio or a TV, especially if they were unhoused or using intravenous drugs.

- Lack of accessible services: “I lived in the Northeast, not too far from Prevention Point, and I would have to go all the way to Center City and wait four or five hours to get tested at the Health Department. This was like, in 2000! It was very scary.”

- Stigma: When Kareem was growing up, he witnessed people in the gay community internalize stigma about HIV testing; there was an assumption that if someone got tested, it was because they were engaging in sex with “too many” people, or that they were using meth.

Desmond Doyley, HIV/Hepatitis C Tester, expresses similar memories of how HIV was discussed—or not discussed at all—as he was growing up in Philadelphia.

“The older Black generation still has the memories of the 80s and 90s of HIV and AIDS. It was not talked about in my household,” he says. “I didn’t know anyone who was living with HIV until my last year in high school. Back in those times, it was still considered ‘bad.’”

Desmond went on to study public health at Temple University and has been working in HIV testing and prevention ever since. “I’m always trying to find out anything I can about HIV that might help our participants, especially since I know how high the rates are among people who inject drugs. I just want to spread awareness. A lot of people don’t want to get tested, especially guys who don’t really want to identify as gay.”

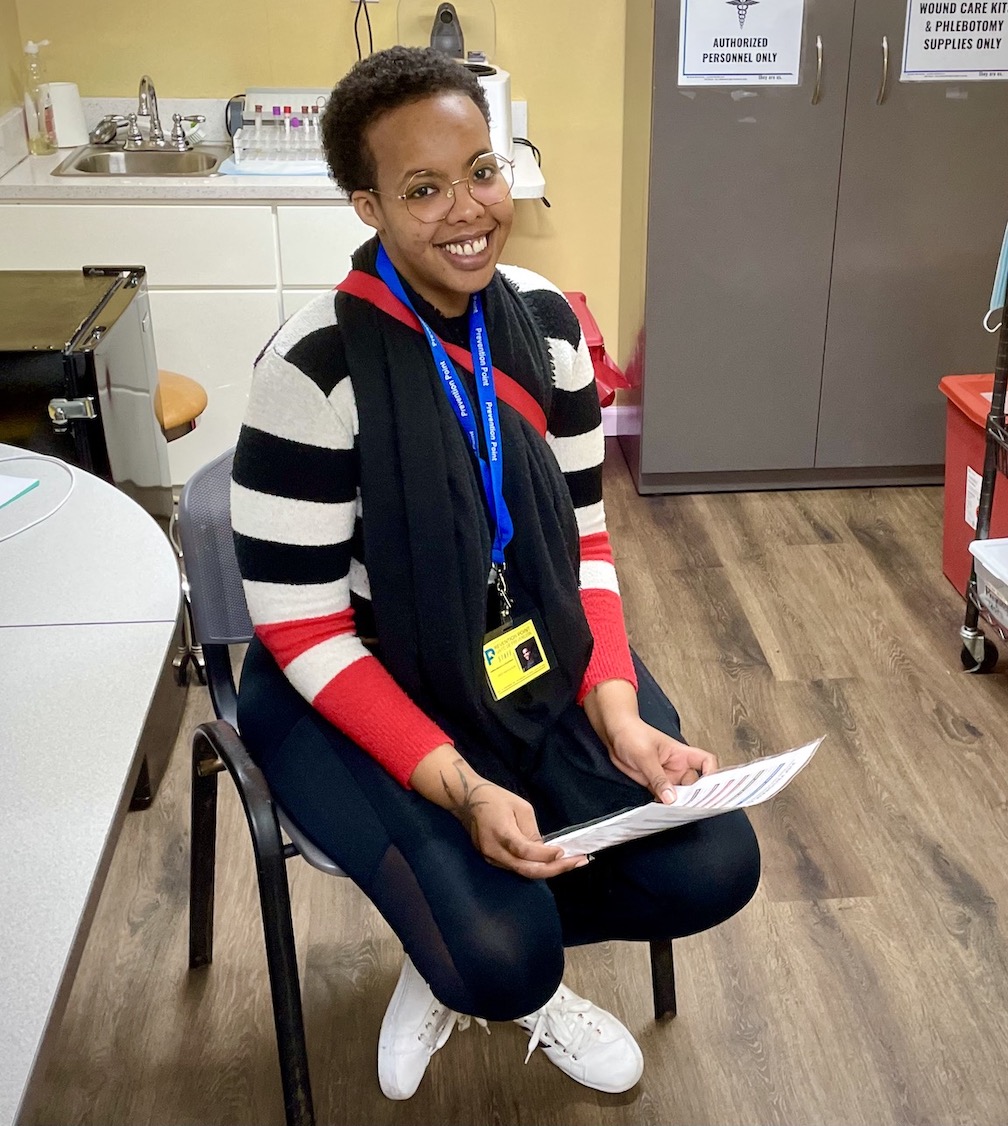

Hallima Docmanov, PrEP Clinic Navigator, and their family came to the United States when they were a child as refugees from Somalia. They initially learned about HIV and its disproportionate toll on Black communities by getting involved with LGBTQ+ organizations and activism in Boston.

"I feel a strong connection to this community and others I’ve worked with. It’s about making them feel visible."

“HIV was never brought up, or any sort of sex talk. These topics are very taboo in my culture. Probably not so much in the new generation, but definitely among the older folks… I was raised very religious as a Muslim and very conservative. Conversations regarding sex and HIV and birth control—that is all information that I had to get from the secular media,” they said.

“I come from an intersection of backgrounds that have always made me feel invisible in this society. I am a refugee, I grew up in poverty, I went to school here in the States as a Muslim wearing a head covering,” Hallima explains. “I feel a strong connection to this community and others I’ve worked with. It’s about making them feel visible… I ultimately see myself in you as you probably see some of yourself in me.”

Hope and hardship

Kareem, Desmond, and Hallima all agree that, while this country has a long way to go towards ending stigma and health inequity, there has been progress.

“When the word about getting tested did get out, the conversation about HIV started happening,” Kareem recalls. “We talked about it in school with friends, and as teenagers we started talking about having sex and using condoms. They were really raunchy conversations, but it was really nice for me to see my friends and peers talking about HIV prevention!”

Kareem and Desmond mentioned Magic Johnson becoming public about his status in 1991 as a moment that prompted conversations about HIV in their communities. Kareem also mentioned the novel Push, the film Precious, the Logo channel, and in particular a show called Noah’s Arc.

“It was a really bad show,” Kareem laughed, “but it centered four young Black gay men who lived in L.A. as they were navigating being professionals, relationships, sex… They were kind of like the Golden Girls but young, Black, and gay. I remember watching Noah’s Arc and the first time my friends and I got tested, we all went to the Health Department together in our best outfits.”

Hallima notes that millennial and Gen Z Muslims are doing the work to lower stigma and increase education around HIV. “There’s a shift in attitude because there’s a generation of people now in this country that is not particularly protected from being exposed to substances or having sex,” they say.

Unfortunately, national HIV testing rates decreased in the pandemic, meaning that it is still difficult to know how COVID-19 has affected rates of HIV transmission on a large scale. Desmond has observed that persisting stigma around HIV prevents young Black men from having open and trusting conversations about sexually transmitted diseases (STIs) and sexual history.

"I tell people, don’t think about how you got HIV because that won’t change. What will change is your mindset and your outlook on yourself."

“I personally feel that sometimes if people are about to have sex and one person asks for a condom, some people feel that they are being judged, like ‘oh they think I have something.’ That’s really why a lot of men don’t talk about condom usage,” Desmond states.

He believes that some of the stigma that used to exist in every-day personal interaction has shifted online, specifically to dating apps like Grindr, where people use harmful terms like “clean” or “not clean” to denote whether they will date someone who is living with HIV.

Desmond and the testing team strive to mitigate the distress that a positive diagnosis can cause for a patient. They emphasize that, with the proper medication, it is possible to lead a normal, long, and healthy life with HIV, and that there is nothing to fear.

“I tell people, don’t think about how you got HIV because that won’t change. What will change is your mindset and your outlook on yourself. You should now put yourself on a pedestal and everything should be about you and your health,” Desmond says.

Solidarity matters

The staff at Prevention Point Philadelphia are hopeful for the futures of people living with HIV, but are also keenly aware that we must continue to center Black voices.

“Now in the time of the pandemic, the focus is on COVID-19. But we are still in a world with HIV, which is also still a pandemic,” Desmond points out.

Hallima emphasizes the importance of looking within Black communities for strength and knowledge, rather than solely relying on systems that have historically not always worked for Black people. “Whether we are immigrants, refugees, or descendants of enslaved people, we have so much in society that is stacked up against us. I think giving our communities grace to understand that it’s not as easy for us to access resources to take care of ourselves is important,” they say. “But we need to figure out how accessibility can bend to how our communities function… There shouldn’t be a one-way approach to care.”

On National Black HIV Testing and Awareness Day, Kareem urges everyone to get tested, regardless of ethnicity or sexual orientation. But, he adds, “Know that you are doing it in solidarity with Black people, because we have been more disproportionately affected by this virus. Black HIV Awareness Day is not just for getting tested. It’s also for us to see, celebrate, and acknowledge people who lost the fight to HIV and AIDS, and those who are still fighting.”